Your cart is currently empty!

Bookazines / Series

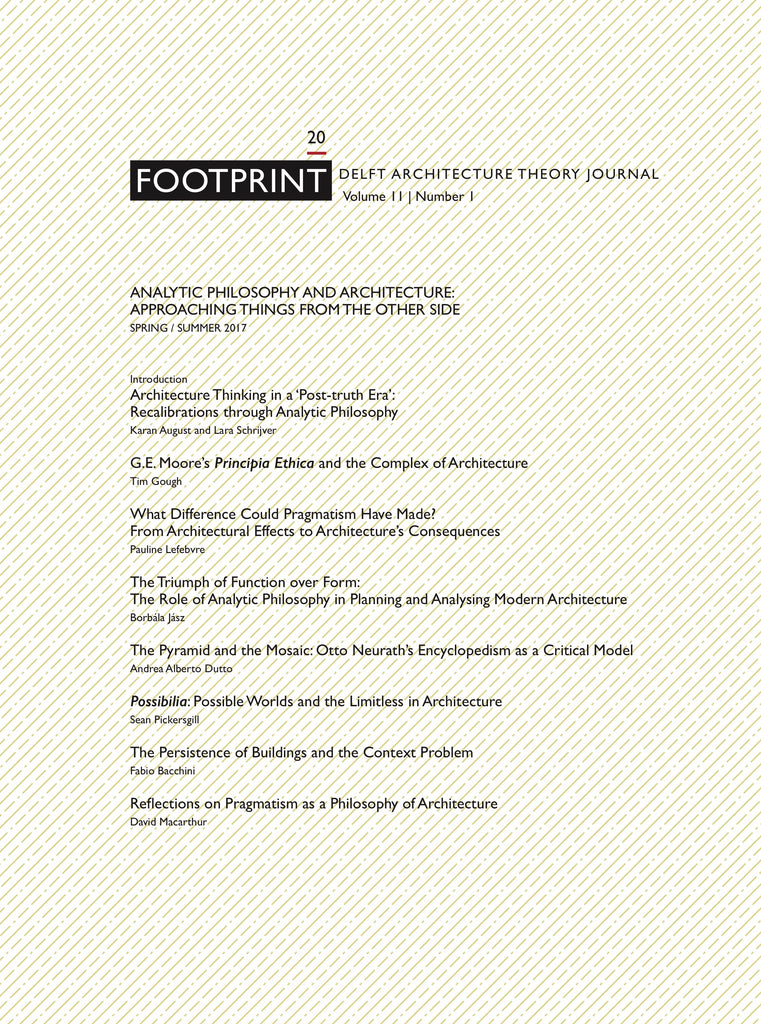

Footprint 20 Analytic Philosophy and Architecture

+++Approaching Things from the Other Side | Vol 11/1 2017+++

+++Karan August, Lara Schrijver (eds.)+++

ISBN

978-94-90322-84-7

Meagan Kerr

Andrej Radman, Nelson Mota

122

19 x 25.7 cm

Softcover

English

Release date: Summer 2017

Published in cooperation with Architecture Theory Chair (TU Delft) and Stichting Footprint: http://footprint.tudelft.nl/

For a subscription: Bruil & Van de Staaij

+++

This issue of Footprint explores the potential role of analytic philosophy in the context of architecture’s typical affinity with continental philosophy over the past three decades. In the last decades of the twentieth century, philosophy became an almost necessary springboard from which to define a work of architecture. Analytic philosophy took a notable backseat to continental philosophy. With this history in mind, this issue of Footprint sought to open the discussion on what might be offered by the less familiar branches of epistemology and logic that are more prevalent and developed in the analytic tradition.

The papers brought together here are situated in the context of a discipline in transformation that seeks a fundamental approach to its own tools, logic and approaches. In this realm, the approaches of logic and epistemology help to define an alternate means of criticality not subjected to personalities or the specialist knowledge of individual philosophies. Rather the various articles attempt to demonstrate that such difference of background assumptions is a common human habit and that some of the techniques of analytic philosophy may help to leap these chasms. The hope is that this is a start of a larger conversation in architecture theory that has as of yet not begun.

"Although thinkers in the field of architecture have embraced ideas emerging from philosophy through the works of continental philosophers since the late 1980s, references to analytic philosophy have remained distinctly absent within architecture history and theory. In part this may be attributable to a perception of analytic philosophy as historiophobic and politically conservative. However in recent decades the philosophical camp is readjusting its relation to language, and notably returning to questions of ethics. Might the finely detailed scholarship of thinkers such as Frege Wittgenstein, Carnap, and Quine, and the more recent scholarship of Jackson, Dummett, and Oswald Hanfling, offer method, style, and findings to the scrutiny of architectural thinkers? Might the emphasis on rule-based systems, clarity of argument and formal logic in the analytic tradition aid in understanding the conditions within which architecture is realized?

Design processes in architecture and urbanism by their very nature have a strongly defined relation to the legislative and regulatory structures of urban master plans, and architectural and structural building codes. For example, in 2010 when asked how he could build such surreal spaces, architect Terunobu Fujimori replied that in Japan structures under ten square meters did not require building consent. Analytic philosophy in this case, may offer a perspective that grasps these particular interventions as experiments in expanding the role of the architect within a field constrained by rules and regulations. In this sense, Fujimori’s response becomes an example of finding alternate solutions for localized obstacles.

In the constraint of the architect’s role, the expertise of the architect is commonly replaced by codes, regulations and guidelines, leading to question if a rule-based computer program can replace the architect? In academia we often play with understandings of architecture that defy the yielding position of our profession. To manifest the profound designs we must gain consent from governing bodies. The design processes of this mundane aspect of working within legislative confinements are undervalued and underdeveloped in academic discourse.

In this Footprint, we suggest that the architecture debate may benefit from the less central traditions of analytic philosophy and of pragmatism, as they offer the means to address finite, localized, and tangible issues within architecture. We especially encourage contributions that approach issues of harnessing arguments within analytic philosophy to reinvigorate and re- appropriate roles of the architect as they navigate the ever increasing complexities of emerging in our field such as the digital augmentation of space, the ethical implications of new materials, the increasing independence of algorithms, the wealth of big data, and questions of the legal necessity to copyright one’s practice."

With contributions by Karan Austust, Lara Schrijver, Tim Gough, Pauline Lefebvre, Borbála Jász, Andrea Alberto Dutto, Sean Pickersgill, Fabrio Bacchini, David Macarthur.

Approaching Things from the Other Side | Vol 11/1 2017

€25.00

Footprint 20 Analytic Philosophy and Architecture

Approaching Things from the Other Side | Vol 11/1 2017

€25.00

Architecture / Bookazines / Series / Theory

ISBN

978-94-90322-84-7

Meagan Kerr

Andrej Radman, Nelson Mota

122

19 x 25.7 cm

Softcover

English

Release date: Summer 2017

Published in cooperation with Architecture Theory Chair (TU Delft) and Stichting Footprint: http://footprint.tudelft.nl/

For a subscription: Bruil & Van de Staaij

This issue of Footprint explores the potential role of analytic philosophy in the context of architecture’s typical affinity with continental philosophy over the past three decades. In the last decades of the twentieth century, philosophy became an almost necessary springboard from which to define a work of architecture. Analytic philosophy took a notable backseat to continental philosophy. With this history in mind, this issue of Footprint sought to open the discussion on what might be offered by the less familiar branches of epistemology and logic that are more prevalent and developed in the analytic tradition.

The papers brought together here are situated in the context of a discipline in transformation that seeks a fundamental approach to its own tools, logic and approaches. In this realm, the approaches of logic and epistemology help to define an alternate means of criticality not subjected to personalities or the specialist knowledge of individual philosophies. Rather the various articles attempt to demonstrate that such difference of background assumptions is a common human habit and that some of the techniques of analytic philosophy may help to leap these chasms. The hope is that this is a start of a larger conversation in architecture theory that has as of yet not begun.

"Although thinkers in the field of architecture have embraced ideas emerging from philosophy through the works of continental philosophers since the late 1980s, references to analytic philosophy have remained distinctly absent within architecture history and theory. In part this may be attributable to a perception of analytic philosophy as historiophobic and politically conservative. However in recent decades the philosophical camp is readjusting its relation to language, and notably returning to questions of ethics. Might the finely detailed scholarship of thinkers such as Frege Wittgenstein, Carnap, and Quine, and the more recent scholarship of Jackson, Dummett, and Oswald Hanfling, offer method, style, and findings to the scrutiny of architectural thinkers? Might the emphasis on rule-based systems, clarity of argument and formal logic in the analytic tradition aid in understanding the conditions within which architecture is realized?

Design processes in architecture and urbanism by their very nature have a strongly defined relation to the legislative and regulatory structures of urban master plans, and architectural and structural building codes. For example, in 2010 when asked how he could build such surreal spaces, architect Terunobu Fujimori replied that in Japan structures under ten square meters did not require building consent. Analytic philosophy in this case, may offer a perspective that grasps these particular interventions as experiments in expanding the role of the architect within a field constrained by rules and regulations. In this sense, Fujimori’s response becomes an example of finding alternate solutions for localized obstacles.

In the constraint of the architect’s role, the expertise of the architect is commonly replaced by codes, regulations and guidelines, leading to question if a rule-based computer program can replace the architect? In academia we often play with understandings of architecture that defy the yielding position of our profession. To manifest the profound designs we must gain consent from governing bodies. The design processes of this mundane aspect of working within legislative confinements are undervalued and underdeveloped in academic discourse.

In this Footprint, we suggest that the architecture debate may benefit from the less central traditions of analytic philosophy and of pragmatism, as they offer the means to address finite, localized, and tangible issues within architecture. We especially encourage contributions that approach issues of harnessing arguments within analytic philosophy to reinvigorate and re- appropriate roles of the architect as they navigate the ever increasing complexities of emerging in our field such as the digital augmentation of space, the ethical implications of new materials, the increasing independence of algorithms, the wealth of big data, and questions of the legal necessity to copyright one’s practice."

With contributions by Karan Austust, Lara Schrijver, Tim Gough, Pauline Lefebvre, Borbála Jász, Andrea Alberto Dutto, Sean Pickersgill, Fabrio Bacchini, David Macarthur.